Using GIS to track the strength of the Socialist Party of America in Minnesota

David A. Shannon's The Socialist Party of America piqued my interest in the geographic reach of the Socialist Party of America. The author details the complex ways in which location, ethnicity, and class background all intersected to create a party with an appeal that was surprisingly broad. On the one hand, it wasn't merely a party of the "far left." As John Reed famously joked, a full third of the party simply thought that Karl Marx was a man who wrote a good anti-trust bill. This was the party's right, whose adherents were often indistinguishable from progressives in the two major parties. On the left of the party were men who found genuinely revolutionary parties after the Russian Revolution. What makes the situation even more confusing is that present stereotypes don't help us at all in comprehending the party's factions. Rural farmers were often to the left of urban workers, foreigners to the right of native-born Americans, and professionals, the wealthy, and even devout Christians could be found on both extremes of the party.

It was a baffling situation which certainly confused contemporaries. (Trotsky, for instance, remarked with some wonder that a convention of the party looked like a convention of dentists.) To help make sense of the party's membership and geographical distribution I turned to a computer. Below are details of my effort to use a geographic information system (GIS) to investigate the geography of the socialist movement's far left in early 1900s Minnesota.

To determine the distribution of the far-left of the socialist party in Minnesota I consulted the News and Views section of the International Socialist Review, which contained letters from readers who often signed with their name and location as well. This section also printed notices about readers who had sent in the most subscriptions. While some of the letters and notices gave names that were used by more than one town or township, and one had a name that did not appear on the 2010 map of town and city boundaries that I obtained from the Minnesota Geospatial Information Office, with a bit of research and reasoned guessing I eventually associated each letter with a town, and each town with a place on a map of Minnesota. This gives us some geographic data points.

The International Socialist Review was published from 1900 to 1918, but only with the replacement of editor A.M. Simons with Charles H. Kerr around 1910 did the publication become the de facto forum of the Socialist Party's left-wing. As it was, I examined issues from 1907 to 1918. I went back no further than 1907 because of the paucity of letters from Minnesota during the editorial reign of A.M. Simons.

I plotted on a map of Minnesota the location of cities whose residents' letters were published in the International Socialist Review. Alone, this approach has a really significant limitation. A town with 100 residents who all wrote into International Socialist Review would be represented the same as a town with one reader who wrote in. However, I tried to look at how other variables correlated with this imperfect set of data.

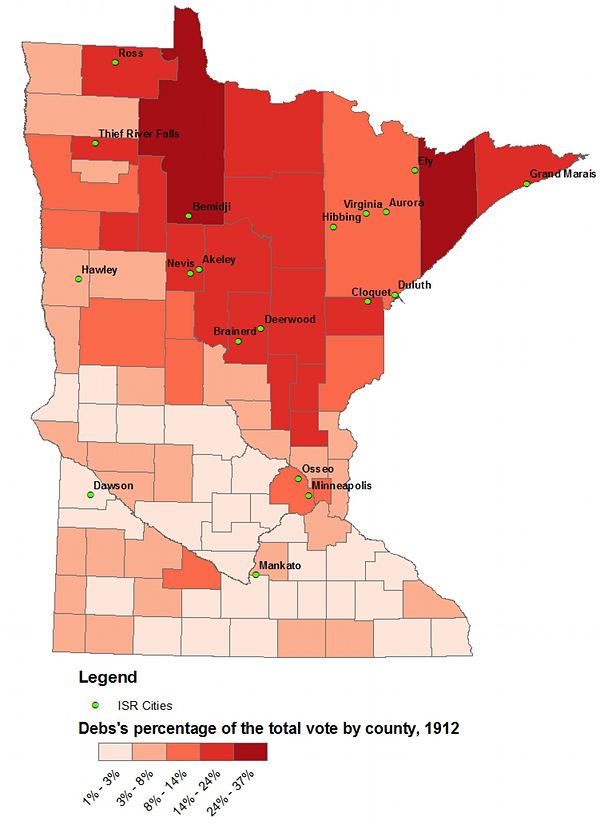

The first and most obvious thing to do was to compare these locations to how well Eugene Debs fared in the county in 1912. Debs was the Socialist Party's candidate in 1912, and 1912 was the Party's best ever electoral showing. To do this I obtained presidential election results by Minnesota county for the 1912 election in Minnesota Votes: Election Returns by County for Presidents, Senators, Congressmen, and Governors, 1857-1977.

(ETA: Joost, who has an interest in Minnesota's interesting history, emailed me to point out a page that has a choropleth map showing Deb's percentage of the 1912 vote by county for the entire U.S.. Thanks, Joost!)

As the above map shows, there is a clear correlation between locations where a person (or more persons) contributed a letter or subscribed to the International Socialist Review and Debs doing well. That is, most cities mentioned in International Socialist Review are in the north of the state, where Debs got the highest proportion of votes. St. Louis County, in the Northeastern part of the state, is something of an exception; despite being the county with the most towns with residents featured in International Socialist Review, the county doesn't quite go for Debs like its neighbors. This is probably because St. Louis County contains Duluth, a large city with a diverse population that didn't quite appreciate Deb's message as much the loggers and miners in the rest of the that part of the state.

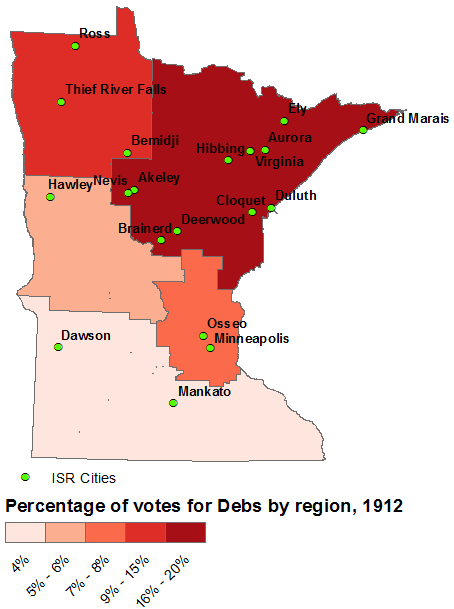

Dissolving Minnesota's counties into somewhat arbitrary regions (I couldn't find any widely agreed-upon standard for this) simplifies things and shows that the state's northeastern region, home to its mines and lumber mills, was a stronghold of the party's left.

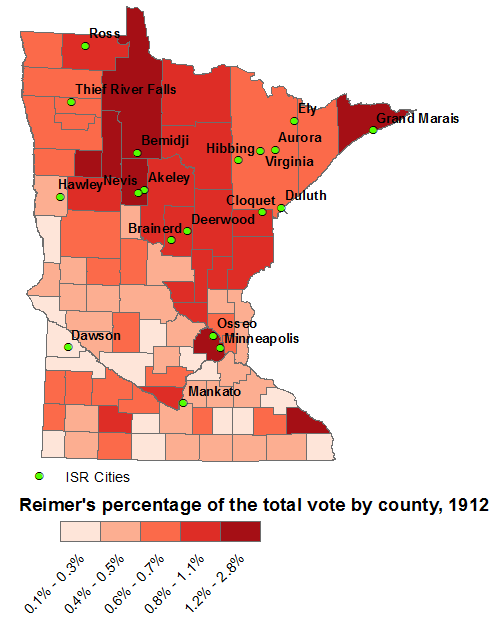

Being that it was 1912, Debs wasn't the only candidate laying claim to the heritage of Marx. The Socialist Labor Party, the minuscule and eccentric second party of American socialism, ran Arthur E. Reimer as its candidate. Reimer mostly did well in the same places as Debs, though there are a few big differences.

The most obvious difference between Reimer and Debs's campaigns is that his appeal was lower, but more uniform geographically. He did as well in the Twin Cities area as he did in the Iron Range, which Debs couldn't claim. Likewise, Reimer did as well in the southern and western parts of the state as he did in the north. Even though Debs garnered 10 or more times the votes in most counties and even beat Roosevelt, Wilson, Taft and the rest in Beltrami and Lake counties, his appeal was mostly limited to the northern portion of the state. Minnesota's farmers don't seem to have been especially radical, possibly because farming was more lucrative in Minnesota than in Oklahoma or Kansas (which had a long history of voting for third parties whose parties and candidates promised agricultural reform, e.g., James Weaver in 1892).

Once I conclusively determined that the northern part of the state was a hotbed for socialism -- and that the more agricultural south wasn't -- I turned to look at some of the factors that might have shed some more light on this dichotomy. Using data downloaded from the excellent National Historic Geographic Information Systems website, I made a few more choropleth maps.

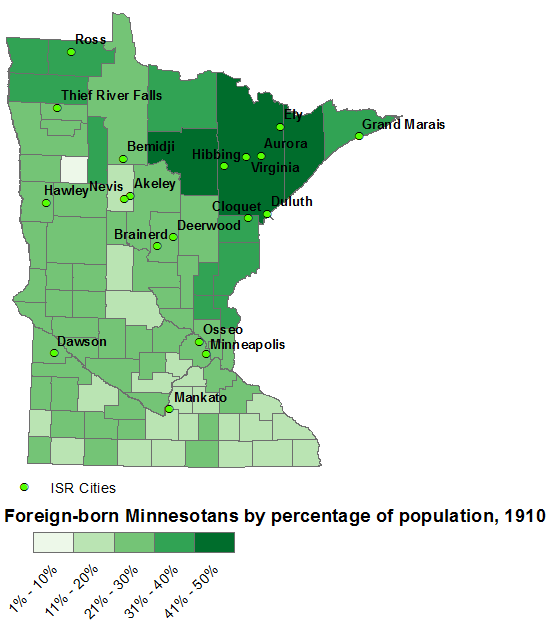

The first of these maps shows the percentage of the population per county that was foreign-born. The data offered by the National Historic Geographic Information Systems website was very specific in that it listed population per country based on a great number of countries of origin; it even divided native-born Americans into those whose parents were born here or abroad. That's very useful and interesting, but for my purposes I simply combined all foreign-born residents into one column and determined the ratio of these folks to native-born Americans.

There is an obvious correlation between counties with lots of immigrants, voting for Debs or Reimer, and submitting letters and subscriptions to the International Socialist Review. As noted at the outset, the correlation between foreign birth and radicalism didn't always hold true. (Especially for states like Kansas and Oklahoma.) In the case of Minnesota, however, it does. Northern Minnesota was, of course, settled by many Finns. Across the country, Finns, Latvians (known then as Letts) and other emigres from the Russian empire were usually among the most radical of Americans. Unfortunately, mapping the ratio of Finns to others per county turned out to be impossible because Finns were counted in the broad category of "others" in the data I used.

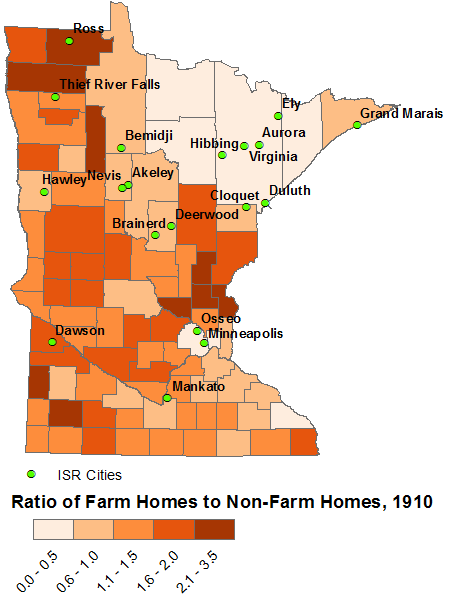

Of course, it's hard to say whether Minnesota's immigrants were already radicalized in Europe or if they became radicalized in America. In fact, it proved difficult to use the data at hand to move beyond the "common knowledge" that Northern Minnesota was a working class area, with lots of folks employed in mining and logging. The 1910 census data provided by the National Historic Geographic Information Systems site lacked any useful occupational breakdowns, so I decided to map the ratio of farm homes to non-farm homes in order to get a very rough picture of what parts of the state were peopled by farmers and what parts of the state were peopled by workers.

If counties with few farm homes could be said to be working class counties, then clearly Debs's strength was in working class countries. But hold on! A glance at the map showing Deb's vote percentage by county shows that some resolutely "red" counties were also had a large proportion of farm homes -- as great a proportion of them as the southern and western parts of the state that showed little interest in Debs's campaign. The one visible difference, of course, is that in Northern Minnesota immigrants made up a large percentage of the population in "farming counties," whereas native-born Americans dominated the farming counties of the south. This suggests that foreign birth, and not just class, was behind the radicalism of northern Minnesota. (Unfortunately, it wasn't possible for me to compare the prosperity of farmers in the north with the prosperity of farmers in the south, though the results might be suggestive.)

Conclusion

It's true that any number of books could in just a few sentences point out that northern Minnesota was radical, working class, and heavily settled by immigrants. Another sentence or two could tie these factors together.

Why, then, spend hours and hours creating maps like I did? For one thing, a single glance at any of these maps tells an important story. The choropleth map of Debs's 1912 votes, for instance, is far more striking than any table or sentence.